It’s been a bit more than a hot minute since I last sent an issue of this newsletter out. And I’m sorry for that. The world sputtered and my brain went astray with it. We’re still in a sputtering place and will be for a while longer, I’m afraid, so I thought I’d try to get back to writing with a piece on a book fits my mood.

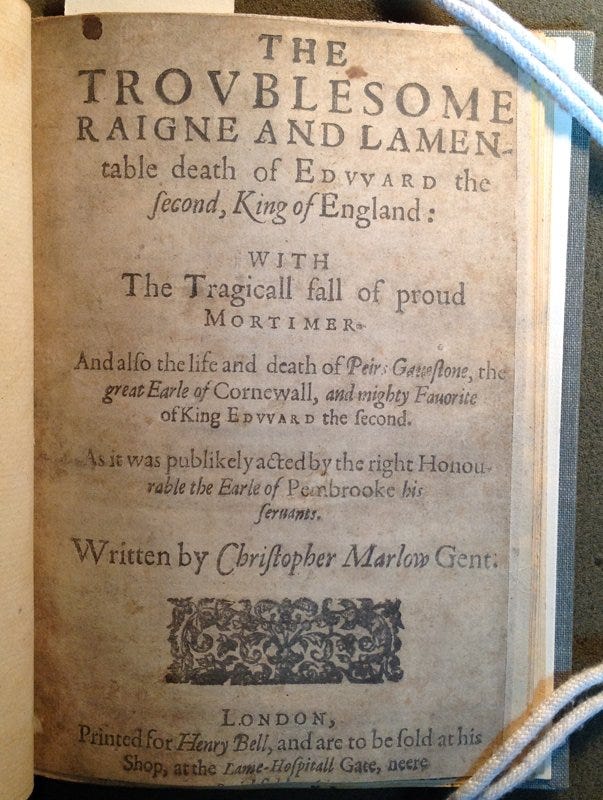

First printed in 1594, Christopher Marlowe’s play Edward II, is a delight, now and then. Here is the title page from the Folger Shakespeare Library’s copy of the 1622 edition, with its expanded title, in case you want to get a sense of what happens in the play:

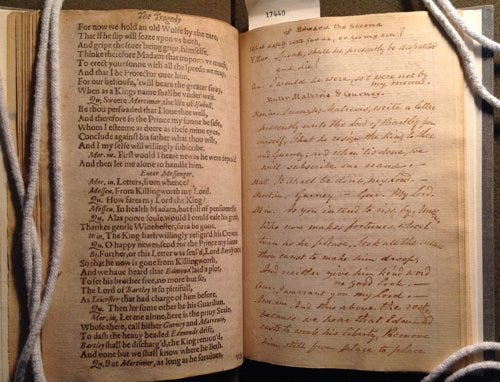

This copy of the play [https://hamnet.folger.edu/cgi-bin/Pwebrecon.cgi?BBID=168665] seems at first like it’s pretty straightforward. It’s trimmed super close at the bottom, and has scattered manuscript notes in it that are mostly corrections to the play text, as in this emendation of “newes” to “now”:

But then, late in the play, after Edward II has been captured and just as Isabel is hinting he needs to be killed off (that is, just around the middle of 5.2) something materially weird happens:

“But Mortimer, as long as he survives,” starts Isabel, and then we find ourselves suddenly in a manuscript continuation, “What safety rests for us, or for my son?”

Clearly, I think we have to assume, this copy is missing the end of the play and an early owner supplied a manuscript text to complete it. That’s not so unusual. The endings of codices are fragile and lots of users completed their texts by copying the missing pages from others. This owner seemed more interested in adding the text than making that text look like the printed book—there’s a headline in a print hand but the text is what I’d describe as a kind of generic 19th-century italic, with some attempts to differentiate speech headings and stage directions by using print and underlining. But it’s not the sort of attempt at a pen-and-ink facsimile that we saw in my earlier post on “book users” [https://sarahwerner.substack.com/p/book-users].

In any case, the book continues along in handwritten pages until, after about 135 lines of the play, right as Edward’s brother is captured in an attempted rescue, we find ourselves in new terrain again:

“Oh miserable is that common weal,” laments Kent, suddenly on page 73 of a 19th-century printed roman typeface. And that’s how the play continues until its end, with Edward III’s ascension and Mortimer’s severed head:

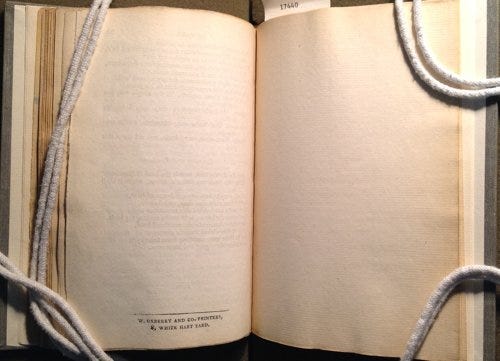

It’s not quite the end of the book, though. We’ve got a colophon for the printed section:

And there’s a binder’s note in the endleaves describing the condition and collation of the volume before being rebound in 1959:

Dorothy Mason’s note helps explain what happened to the 1628 volume: the last two gatherings (I and K) disappeared, which makes some amount of sense if we assume the book hadn’t been firmly bound in its early years. Sometimes a leaf or two tears off, but it’s also easy for entire quires to separate—once parts of a quire go missing, the other leaves become more vulnerable, and next thing you know, your book stops in the middle.

But why is this copy completed with both manuscript and 19th-century text? Why not just one or the other?

The answer lies again with quires. Go back and look at the switch from manuscript to print. Do you notice at the bottom of the first printed leaf the little letter “K”? That indicates that it’s the first leaf of its quire. Maybe the owner found it easier to disassemble a contemporary book along its binding structure and then fill in the gap with handwritten leaves so that the text lines up properly. (The 1622 text stops in what is the middle of page 68 of the 1818 text, an awkward doubling up of passages were page 68 simply to be tipped in following leaf H4.)

And what is this printed copy the owner used to perfect the earlier text? The first hint is the colophon: “W. Oxberry and Co., printers / 8, White Hart Yard.” William Oxberry was an actor and editor who published a series of early playtexts, including editions of Marlowe’s plays in 1818. Here’s the title page from a complete copy of Oxberry’s edition (bound in a volume with other Marlowe plays) from the Folger’s collections [http://hamnet.folger.edu/cgi-bin/Pwebrecon.cgi?BBID=35452]:

And here’s the beginning of the K quire on the right of this opening, looking just like what we see in our sideways copy:

I am not sure when this book was transformed into its current state, but I am sure that it was mid-19th-century, when 16th-century printed texts were still objects to be read and used rather than preserved as is, and when a book printed in 1818 was ordinary enough to be disassembled. I suppose we might wonder why, if the owner had a complete 1818 edition of Edward II, they felt the need to complete their 1628 copy of the play this way, but it also seems obvious to me that they valued the early quarto for its text and wanted to be able to read it on its own.

Sometimes things go sideways and you work with what you have, making decisions about what is the most important to you in shaping it for your own use. Books are no exception, old or new.

Some notes

If you haven’t read Edward II before, or if you want to reread it, or maybe stage it, you can read it online for free in the Folger’s A Digital Anthology of Early Modern English Drama at https://earlymodernenglishdrama.folger.edu/view/1640/Ed2. I also love Derek Jarman’s 1991 film of it, so if you can find that streaming, go enjoy Tilda Swinton in all her glory as Isabel, not to mention Annie Lennox serenading Edward and Gaveston with some Cole Porter. The early 90s rage that Jarman felt about homophobia and advocacy for gay rights will resonate today, too.

The catalog record for the copy I discuss here is at https://hamnet.folger.edu/cgi-bin/Pwebrecon.cgi?BBID=168665; the Folger hasn’t imaged the copy and my own photos are reproduced here in very reduced scale, but if you want to seem hi-res version of what I took (years ago, to be honest, and so maybe not fully ideal), just drop me a line.

The 1818 Oxberry edition has been digitized in full by the Bayerische StaatsBibliothek and you can read it at http://mdz-nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:bvb:12-bsb10747544-5.

And if you’re interested in the print history of early English plays for any reason, I highly recommend taking a look at DEEP: The Database of Early English Playbooks (http://deep.sas.upenn.edu/).

Thanks, and see you soon!

I know I’ve said “see you soon” before and then months elapsed, but I really am trying to figure out ways to write this newsletter even without access to rare books in person. I can’t promise anything other than sporadic delivery at the moment, but I am grateful to those of you who are reading this and sticking by. Writing about these things brings me a lot of joy, and I hope reading them brings something good to you, too.

I hope you all are doing as well as you can be in this world and that even when things go sideways, your p’s and q’s are all in the order you want them to be.

Sarah.

That was fascinating! Thank you and we missed you.

Plus, of course, there's Derek Jarman's fabulous film version of the play.