Blanking out

What are blank pages and why would you want to look at them?

My mind is a blank, time is a blank, who even knows what the future will bring. And so what better time is there for showing you blank pages!

A blank page, you ask? What is there to say about that? It’s just blank. It’s empty. It’s the plague, Sarah, please be more entertaining than that.

Oh, trust me, I know times are hard, but blanks are always entertaining.

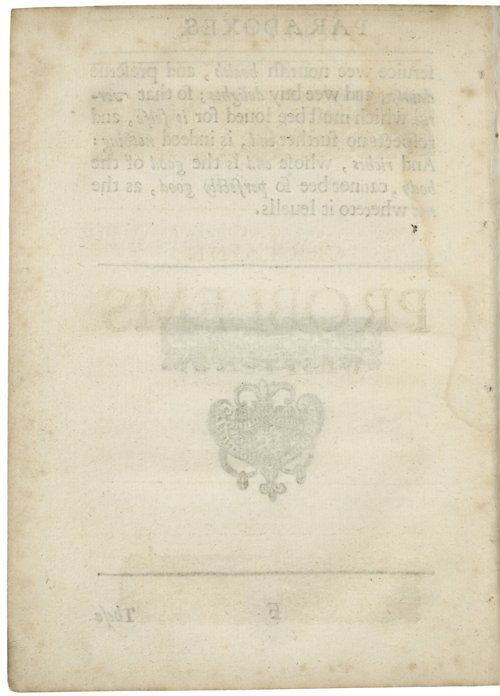

Here’s a good blank page, for instance. It’s a blank leaf from the Folger copy of John Donne’s Iuuenilia: or Certaine paradoxes and problemes that comes between the Paradoxes section and the Problems section (aka Folger STC 7043.2 sig. F1v):

Is it empty? Oh my goodness no! For starters, you’ve got some nice bleed-through of the ink from the recto side of the leaf. This is not unusual in printing: ink is dark, paper is light, and you can often see the reverse side, but you usually only notice it when one side has blank areas. Here you can clearly see the running title “Paradoxes,” some rulings, a block of text, a nice tailpiece and border, a signature mark and a catchword down at the bottom. (That catchword, “These,” is weird, you might be thinking, and you’re right, it is.)

But what’s that “PROBLEMS” in the middle of the page? Not bleed-through, but off-set ink from the facing page. How can you tell the difference? Well, you might notice the color, which is a bit browner, or you might notice that the hand-press can’t print overlapping type unless you run it through the press twice—two different pieces of metal can’t occupy the same place at the same time, that’s just physics.

So, in any case, is that blank empty? No, obviously!

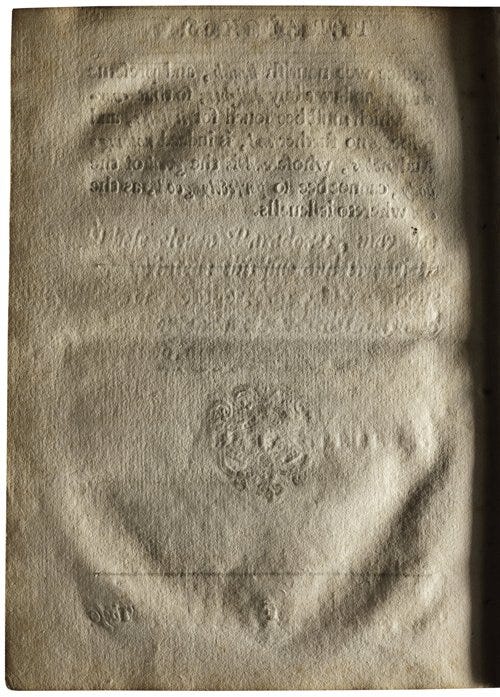

But it gets even better, because there’s more that we’re not seeing. Here’s an image of the same blank page taken under raking light so that you can see the topography of the page:

The first thing you might say to yourself is, damn that leaf is wrinkly! And yes, it is. Paper really can have a topography. Not all paper is so cockled, but some is. And you can see very clearly here that ink isn’t just laid on top of paper, but pressed into it. All that text leaves impressions and extrusions that show up under the right lighting. In fact, those impressions from metal type are there whether they are inked or not. Look carefully in the middle of the page for some new text that we didn’t see before. Do you see, right above the middle rule, where it reads “These eleuen Paradoxes, may”? What in the world?? That wasn’t there before! (I want to focus on blanks and not blind type, so I’m going to send you to a piece by R. MacGeddon, aka Randall McLeod, for a proper reading of what’s going on there, but the gist of it is that some editions have an inked imprimatur there and some do not.)

Not all blank pages are that exciting, in part because most of them are not imaged under both flat and raking light. But all of them have something going on. There might be inscriptions, or evidence of folds and repairs, or interesting textures. I’ve included a handful of blank pages on EarlyPrintedBooks.com and if you’re looking for something to do—or for something for your students to do—you might want to take a look at those and see what you notice. Look at them separately, compare them with each other, think about what we might or might not learn from those not-empty spaces. Many of the blanks on the site include a headnote from me that says something about them, but not all. And you can always go on a scavenger hunt through my list of early modern digital collections to find other examples of blank features. (Now that I think about it, I should probably create a worksheet for an exercise on blanks. I’ll do that soonish.)

But before we go, I want to share two other blanks with you. These are blanks that really do try hard to be empty spaces, and it’s because of that effort that they are so very full of meaning.

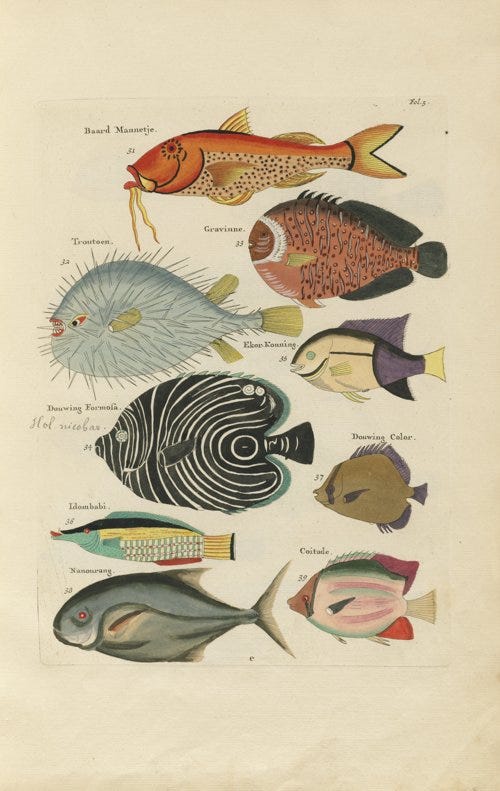

This first example is from Louis Renard’s Poissons, ecrevisses et crabes, de diverses couleurs et figures extraordinaires, an 18th-century book of hand-colored plates illustrating over 450 species of fish and other sea creatures from the East Indies. Since the book consists primarily of copper plate illustrations printed on a rolling press, the versos of those pictures are blanks. In the Harvard copy that was digitized, that means that you can see a glorious image like this….

which is followed by one like this:

If you view the work on the Biodiversity Heritage Library site, you can end up flipping through a book like this:

I get it. Digitizing all those blanks would nearly double the number of images that have to be taken and processed. It adds to the time and cost of the project. And for what? It’s just empty space!! I mean, I guess it’s just empty space. We don’t know. We’re told it’s blank, but we know better, don’t we? I’d guess if you were interested in hand-coloring, in particular, you might learn something from the versos, but we aren’t going to find that out from looking at these images.

Here’s the second example, one that I find pretty hilarious, to be honest, and full of anxieties about imaging blanks. This is from a Charles Kean scrapbook now owned by the Folger. It’s a scrapbook of around 650 watercolors and engravings of Shakespeare characters, with each picture carefully cut out and pasted together onto leaves in the volume. And, as you would guess, the versos of these leaves are blank. So here’s the recto of the 15th leaf:

And here’s the back of that same leaf:

You saw that coming, right? But did you notice the difference between how the Renard digitization shows its blanks and how the Kean shows its? Let’s look at them side-by-side:

The Renard, on the left, is pretty much a beige rectangle with black sans-serif text. The Kean, however, is… textured, I guess? The Kean looks like a page of paper, kind of. Only what paper is being represented? The paper is so weirdly specific. It’s got a fold across the middle, a sort of crease at the top, some cockling along the right edge. There are clear horizontal wire lines, although no chain lines, I don’t think. I tend to start being unsure what I’m seeing and what I’m imagining when I stare at it too long.

If you look at the bits of paper we can see in the volume—like this page (fol. 62r), for instance, which only has one small illustration pasted on—you can see that what we can glimpse of the paper used in the scrapbook doesn’t look like the representational blank page being used. Is it a crumpled up modern laid paper that was imaged for this purpose? It is clearly labeled to make us see it as a substitute, and yet I can’t help but wonder why such effort was put into making a fake blank instead of just using a beige rectangle. What’s being signalled here about the value of blankness and the fear that what’s blank might signal something wrong?

I told you blanks were full of mysteries. I hope you will now join me in my obsession.

Some notes

The MacGeddon piece is full of very fun details about bearing type—that is, type that is used to even the surface of what’s being printed so that the platen doesn’t tilt and crack the type. It’s probably not easy to find at the moment, since it’s in a printed collection, but if you want to be able to teach with it alongside this, hit me up (sarah@earlyprintedbooks.com) and I’ll see if I can help. (Hint: I can.) For citational purposes: MacGeddon, R. [pseud. Randall McLeod] “Hammered.” In Negotiating the Jacobean Printed Book, edited by Pete Langman (Ashgate, 2011), 137–99.

The fish book is pure delight, and you can read about it in this BHL blog post, “Renard’s Book of Fantastical Fish.” What I really want to do in this at-home twiddling-my-thumbs time of anxiety is make all sorts of things from this public domain digitization. Notebooks! Pillows! Maybe a t-shirt? I don’t know but I will tell you when it’s done.

If you are now teaching or learning at home, friends, I wish you all my best in adjusting to this world. My last EPF post was an open-thread discussion about how to teach material texts online, and you might find some ideas in there. I also updated my page of digitization examples and you might find ideas in there for talking about material texts through digital interfaces. It’s not the same as holding a book in your hand, I know, and I’m sorry that your plans are now all awry.

Thanks and see you soon!

Once again, time is a mystery, and we are only human. I’ve been making a lot of plague jokes and doing a lot of staring into space because that’s how my brain is coping with everything. I hope you are finding your own ways of coping and that through all of this you are kind to yourself and to others. We are only human, and that’s a pretty great thing.

Stay indoors, be healthy, and mind your p’s and q’s!

Sarah.

The BHL book brings up an interesting point: as BHL is a consortium, the members are able to make their own calls (TO AN EXTENT... beyond this we get into a lot of nitty gritty) on how they digitize. Smithsonian Libraries, for example, makes a point to scan all pages front and back, while other partners (such as Harvard MCZ, apparently) don't. It raises an interesting point about who libraries think are looking at their digital objects: BHL's core goal is communicating biodiversity literature, not necessarily the physical objects, so scanning blanks was not a priority for them. On the other hand, the rare book librarians at Smithsonian Libraries have had a LOT of input on scanning, so our digitization crew scans blanks, pastedowns, flyleaves, the whole shebang!